Pine Hill has been hitting the reset button for a very long time.

Long before cabin weekends, ski crowds, or people claiming they’re “off-grid” while live-posting the experience, this valley was already famous for two things worth crossing mountains for: clean air and pure water. And maybe a third, an easy urge to stay a while.

Before it was Pine Hill, Native Americans knew this land as Kawiensinck. The name was shared by two Esopus men, John Paulin and Sapan, with interpreter Thomas Nottingham and recorded on a 1771 map for the Hardenburgh Patent. In other words, this place didn’t begin with a charming inn or a tourism slogan. It was known, named, and traveled through long before anyone thought to market it.

Back then, the mountains were the map. Ridges dictated routes. Water decided where you stopped.

Picture the Catskills around 1740: no GPS, no coffee breaks, no “we’ll be there in twenty minutes.” Just wilderness and commitment. A guide from Shokan, Henry Bush, led Robert Livingston and his son through the region, crossing Pine Hill on a rugged route that eventually became the Ulster and Delaware Turnpike. Cutting a road through this terrain wasn’t convenient, it was a declaration.

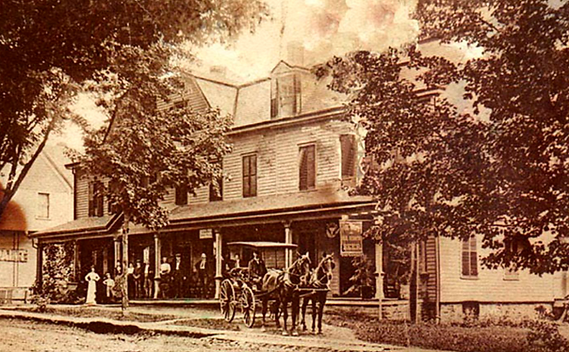

Before 1800, Aaron Adams made the first known clearing in Pine Hill and built what is believed to be the upper portion of today’s Colonial Inn. A clearing isn’t just land, it’s a decision. That was the moment Pine Hill began shifting from a place you passed through to a place you came back to.

Industry followed. In 1831, Frenchman Augustus A. Guigou built the town’s first tannery behind what would later become the Funcrest. It burned in 1858 and was never rebuilt, one of several times fire would rewrite Pine Hill’s plans. The Catskills have a way of politely reminding humans who’s in charge.

By the 1850s, stagecoaches ran regularly from Kingston to Pine Hill. On a good day, the seven-hour trip gave travelers plenty of time to regret their choices, confirm them, and then run out of alternatives. Stops included the Colonial Inn, and once visitors arrived, the mountains worked their magic: clean air, cold water, and a sudden willingness to slow down.

Locals doubted a train could ever climb into Pine Hill, but in 1872, the Ulster and Delaware Railroad proved them wrong. The approach included the famous Horseshoe Curve, offering passengers a sweeping view of the valley below. For many, it felt less like an arrival and more like an introduction.

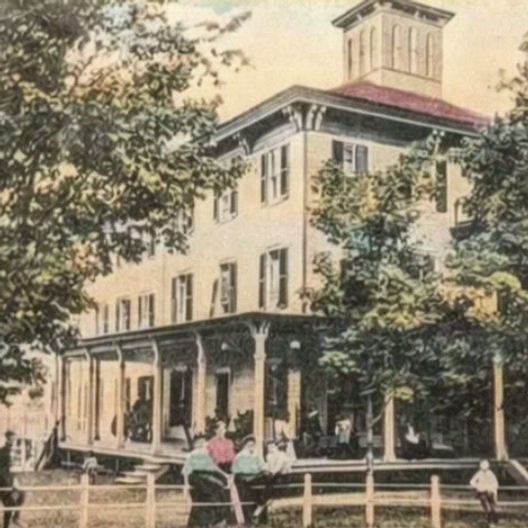

The railroad changed everything. Hotels, boarding houses, and visitors poured in, drawn by Pine Hill’s greatest hits: air you could actually breathe and water clear enough to brag about. The hamlet earned the nickname “the Saratoga of the Catskills.” Victorian-era hotels flourished, porches became prime real estate, and Pine Hill entered its golden age as a health and resort destination, back when wellness was a lifestyle, not a hashtag.

Around 1885, the Crystal Spring Water Company began bottling Pine Hill’s spring water and shipping it to New York City, six to nine rail cars a week at its peak.

Bottling continued into the early 1900s, including soda, until a 1933 explosion and fire destroyed the plant. Fourteen firemen were overcome by toxic gases, and the industry ended. The spring, however, never stopped. It still supplies Pine Hill today, quietly doing what it’s always done.

Incorporated as a village in 1895, Pine Hill thrived. There were newspapers, churches, shops, mills, a photo studio, bowling alleys, and a fire department, because wooden hotels and optimism only get you so far. Recreation flourished too: Pine Hill Lake (lost in the 1951 flood), one of the region’s first silent movie theaters, early winter skiing via a rope tow behind the Colonial Inn. Pine Hill wasn’t just hosting visitors, it was entertaining them.

Like many resort towns, the mid-20th century brought change. Rail travel faded. Big hotels closed. Crowds thinned. In 1985, Pine Hill dissolved its village status and returned to being a hamlet.

But here’s the part people fall for: Pine Hill never disappeared. It kept its bones. Its streets. Its sense of memory.

In 2012, the Pine Hill Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, recognizing 125 contributing buildings, including the Morton Memorial Library and the Elm Street Stone Arch Bridge. Preservation here isn’t about freezing time, it’s about letting you walk through it.

Today, Pine Hill is still shaped by ridges, water, and the paths people take to get here. The air still feels like it can fix your mood. And with renewed landmarks, growing trails, and new traditions—like the restoration of The Wellington, the upcoming renovation of the Pine Hill Arms and Belleayre Lodge, the expanding Rail Trail along the abandoned Horseshoe Curve, and 2025’s inaugural Pine Hill Pride, it’s quietly finding its momentum again.